Quality sleep is important for many aspects of health, yet many people struggle to get enough sleep every night. This post will walk you through the science-based health benefits of sleep.

What is Sleep?

Definition

Sleep can be defined in many ways. According to one definition, sleep is a natural and reversible state of reduced responsiveness and relative inactivity, accompanied by a loss of consciousness of one’s surroundings, dreaming, and characteristic brain activity patterns. It is usually seen as essential for restoring and recovering vital bodily and mental functions [1].

Sleep occurs in regular intervals. Humans have a consistent need for sleep, so a loss or delay in regular sleep results in subsequently prolonged sleep [2].

The Stages of Sleep

There are two types of sleep: non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep.

Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep

REM sleep is characterized by high-frequency low-voltage brain electrical activity (as measured by an electroencephalogram (EEG)) and bursts of rapid contractions of eye muscles, causing the eyes to move rapidly. Dreaming is thought to arise during this phase of sleep [3].

Studies suggest that a healthy person’s normal night of sleep typically includes 4-5 distinct REM cycles. REM sleep accounts for about 20% of the total time spent asleep [3].

Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep

Most of a night’s sleep is spent in NREM sleep, which is further divided into 4 sub-stages (stages I-IV) [1]:

- Stage I (N1), described as the lightest stage of sleep

- Stage II (N2), defined by the emergence of specific types of peaks in the EEG spectrum (known as K-complexes and sleep spindles). N2 sleep typically accounts for more than half a night’s sleep.

- Stage III and IV (N3 and N4), the deepest stages of sleep that are characterized by slow brain waves called delta brain waves. Together stages III and IV are referred to as slow-wave sleep (SWS).

Are All Sleep Stages Equally Important?

According to one hypothesis, slow wave sleep (SWS) may be the most restorative stage of sleep that might have the greatest impact on immune regulation [1].

Throughout one period of sleep, both REM and NREM sleep alternate cyclically. The first progression through the four non-REM sleep stages typically takes 70-100 minutes in most healthy people, according to the research [3].

Both REM and NREM sleep are important. Irregular cycling and/or the absence of sleep stages have been associated with sleep disorders [4].

Preliminary data suggest that people with inflammation tend to have trouble getting enough deep sleep (stages 3 and 4). Scientists hypothesize that inflammation may result in HPA axis activation and higher CRH, which might reduce deep sleep. More research is needed to verify this link [5].

When to See a Doctor

This post focuses on the science of sleep and its scope is informational only.

If you are experiencing sleep problems – including those of insomnia, irregular sleeping patterns, or obstructive sleep apnea – it’s important to talk to your doctor, especially your inability to get quality sleep is significantly impacting your daily life.

Your doctor should diagnose and treat any underlying conditions causing your symptoms.

Research Limitations

The majority of studies covered in this article deal with associations only, which means that a cause-and-effect relationship hasn’t been established.

For example, just because anxiety has been linked with poor sleep or insomnia doesn’t mean that anxiety is caused by sleep issues. Even if a study did find that sleep deprivation contributes to mood disorders like anxiety or depression, it is unlikely to be the only cause.

Remember, complex disorders like anxiety always involve multiple possible factors – including brain chemistry, environment, health status, and genetics – that may vary from one person to another.

With this in mind, let’s take a deep dive into all the ways that sleep might impact brain, metabolic, heart, and immune health.

Sleep & Brain Health

1) Memory and Cognitive Function

Scientists explain that sleep is essential for effective cognitive function. It’s thought to support both cognitive function and memory, while a lack of sleep is detrimental to cognitive function [6].

Sleep loss diminishes many cognitive abilities including attention, language, reasoning, decision-making, learning, and memory [7, 8, 9].

In children, shortened sleep duration, especially before the age of 41 months, is associated with lower cognitive performance and developmental tests [10].

Adults completely deprived of sleep showed deficits in short-term memory and in their ability to perform unconscious and repeated movements from memory, such as bicycle riding and shoelace tying [11].

Scientific studies suggest that sleep may support cognitive health by strengthening and stabilizing new memories acquired before sleep. It’s also thought to help reprocess relatively fresh memories and integrate them into the pre-existing network of long-term memories [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17].

Some scientists hypothesize that a short period of sleep prior to learning might enhance the capacity to remember new information [18].

Limited studies also suggest that naps can reduce sleepiness and improve cognitive performance, particularly in people who are not getting optimal sleep at night [19].

2) Clearing Metabolic Waste

The glymphatic system clears metabolic waste from the brain while the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord cells (cerebrospinal fluid) removes beta-amyloid metabolites from the brain [20, 21].

One theory states that sleep may stimulate the glymphatic system and the cerebrospinal fluid to clear metabolic waste from the adult brain [22].

Scientists hypothesize that when people sleep well, their glymphatic system can effectively remove cellular waste byproducts that have accumulated outside and inside of brain cells. More human research is needed to verify this theory [23].

3) Supporting Brain Cells

According to limited studies, levels of oxidized glutathione, increase at the end of the day and during sleep. Oxidized glutathione is thought to be a sleep-inducing substance that may counteract glutamate toxicity and support the survival of brain cells. However, human studies are lacking to confirm this [24].

4) Mental Health

Studies point to a tight link between mental health disorders and poor sleep, but research hasn’t yet pinpointed what’s cause and what effect. In turns out that the relationship between mental health and sleep is not a straightforward one.

Evidence shows that most patients with depressive disorders also have sleep disturbances. Difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep or both have been reported in about three-quarters of all depressed patients [25].

On the other hand, patients with persistent insomnia have a 2 to 3.5-fold increased risk of developing depression compared to people without insomnia [26, 27]. About 73% of adolescents with major depression also reported insomnia and hypersomnia (excessive sleep) [28].

Sleep disturbances have also been associated with other psychiatric illnesses, including [29]:

- generalized anxiety disorder

- panic disorder

- posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Also, 32% of people

who claim to have “brain fog” also have a diagnosed sleep disorder, most commonly insomnia, sleep apnea or restless leg syndrome [30].

In mental health practice settings, children and adolescents with ADHD frequently reported sleep problems, particularly difficulty in initiating and maintaining sleep [31].

Most antidepressant medications suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, but how this impacts symptoms isn’t clear. Reducing REM sleep is sometimes seen as beneficial in people with mood disorders since too much REM sleep is thought to worsen mood and memory in people who are anxious or depressed [32, 33].

Sleep & Metabolic Health

5) May Control Appetite

Scientists think that two hormones mainly control appetite: leptin and ghrelin. Leptin typically decreases your appetite, while ghrelin increases it. However, leptin can also increase appetite [34].

Plus, leptin also decreases with weight loss and mild starvation. In this sense, lower leptin is thought to signal a state of scarcity and it will increase food intake. Sleep loss might have a similar effect [34].

So while science suggests that proper sleep helps maintain a healthy appetite, the interplay between sleep and these hormones is less clear.

In both animals and humans, sleep loss is associated with decreased leptin and increased ghrelin levels, leading to an increased appetite [35, 36].

In sleep-deprived young men, leptin levels decreased by 18% and ghrelin levels increased by 28% causing a total increase in appetite of 23% when compared to the levels present after healthy sleep [37].

Also, leptin levels are directly proportional to the amount of body fat a person has, and the impact of sleep might be insignificant. More research is needed [38].

6) Weight Loss

Unhealthy sleep is associated with obesity and eating problems [39].

A sleep duration of fewer than 6 hours per night has been associated with a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) [40, 41].

A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analysis showed that adults who slept less than 7 hours per night were more likely to be obese [42].

People who slept only 5.5 hours per night lost 55% less body fat and 60% more fat-free mass (e.g bones and muscles) compared to people who slept 8.5 hours per night [43].

However, whether or not sleep problems can directly cause weight gain is still unclear. Despite this, sleep deprivation worsens general well-being. That’s why getting enough restful sleep should be on a list of healthy lifestyle interventions in people looking to lose weight.

7) Insulin Sensitivity

Sufficient quality sleep may support sugar and insulin balance in the body. According to one study, glucose tolerance was significantly lower in sleep-deprived young men compared to those who slept well [44].

Sleep deprivation is also hypothesized to result in reduced insulin sensitivity [45].

In a cohort study, men reporting short sleep duration (less than or equal to 6 hours per night) were twice as likely to develop diabetes than those men who reported 7 hours of sleep per night [46].

In the same study, men who reported long sleep duration (greater than 8 hours of sleep per night) were three times as likely to develop diabetes than those who reported 7 hours of sleep per night [46].

Therefore, both short and long sleep durations have been linked with an increased risk of developing diabetes. Larger, multi-center human studies are needed [47].

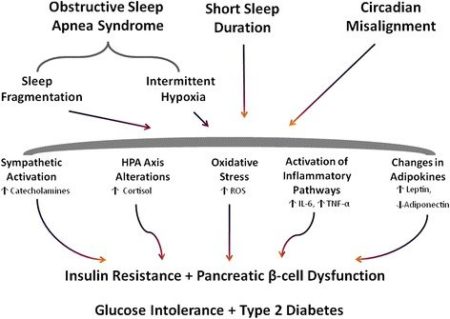

Sleep-related metabolic pathways hypothesized to influence the development of Type 2 diabetes

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4381534/

8) Liver Health

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a disease characterized by too much fat in the liver of people who drink little to no alcohol. In the long run, it can lead to cirrhosis (scarring) of the liver.

Short sleep duration and poor sleep quality were associated with an increased risk of NAFLD in one study [48].

Another study suggested an association between long nighttime sleep and a modestly increased risk of NAFLD [49]

Sleep & Cardiovascular Health

Scientists believe that sleep influences cardiovascular function in both healthy people and in those with heart diseases [50]. Getting quality sleep may reduce heart disease risk, according to limited evidence; unhealthy sl eep has been associated with heart disease [51].

9) Blood Pressure

In one study, sleep duration of fewer than 5 hours per night was associated with an increased risk of high blood pressure (hypertension) in subjects between the ages of 32-59 years old [52].

According to some researchers, a higher risk of hypertension coupled with increased sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system activity caused by a lack of sleep may underlie the relationship between sleep deprivation and heart disease. More research is needed [47].

10) Coronary Heart Disease

Both abnormally short and long self-reported sleep duration have been independently associated with a modestly increased risk of coronary heart disease [47].

In this study, men who sleep 4 hours or less per night were more likely to die from coronary heart disease than those who sleep 7-7.9 hours per night [53].

On the other hand, women reporting 9 or more hours of sleep per night had higher risks of developing coronary heart disease than those with 7 – 9 hours of sleep [54].

Larger studies are required.

Sleep & Immune System Balance

Good sleep supports a healthy immune response, while a lack of sleep is hypothesized to worsen inflammation and autoimmunity.

11) Immune Defense

Scientists think that adequate sleep strengthens immune function and reduces excess inflammation [55, 56].

Lack of sleep increases susceptibility to infections and worsens the ability to fight off bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections [57, 58].

Good sleep may also enhance the immune system’s ability to remember a previous infection and mount a more effective response in the case of re-infection [57, 59]. This is the proposed mechanism of vaccine adjuvants, and thus quality sleep is being researched as a lifestyle intervention that may improve the response to vaccination.

Limited evidence suggests sleep deprived people have higher levels of circulating immune cells (T cells and NK cells) and inflammatory cytokine levels (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-ɑ, etc.) [58]. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines may, in theory, contribute to inflammatory diseases.

12) Autoimmune Disease

Sleep Deprivation Reduces Regulatory T Cell Activity

T regulatory cells (Treg) suppress inappropriate immune responses and prevent the immune system from attacking the body’s own cells. This is also called self-tolerance [60]. Disruption to this process is hypothesized to cause autoimmune diseases, though more work is needed to prove it [61].

In one study that experimentally sleep deprived healthy people, treg activity was reduced. The authors suggested that sleep deprivation may contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases [62].

Sleep Deprivation May Increases Inflammation and Th17 Immune Responses

Sleep deprivation is hypothesized to increase proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-ɑ, and IL-17. Large human data are still lacking to confirm this, though.

Some scientists think that disordered sleep may induce systemic inflammation and activate Th17 cells, thereby leading to autoimmune diseases [63, 64, 65]. In one preliminary study, the Th17 cytokine IL-17 remained elevated following sleep deprivation, even after recovery for 7 days [66].

Read this post to learn more about Th17 and autoimmunity and factors that may reduce Th17 dominance.

Th17 activation has been associated with several autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease and multiple sclerosis [64].

Studies show that mice with chronic sleep deprivation develop an autoimmune disease that strongly resembles Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Human data about this are lacking [67, 68].

Sleep & Hormonal Balance

13) The Stress Response (HPA Axis)

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is also described as the stress response axis since it can be activated in response to physiological or emotional stress [69].

Sleep, particularly slow wave sleep, seems to inhibit the HPA axis and cortisol secretion in animals [70].

On the other hand, sleep loss and sleep disruption activate the HPA stress response axis and, thus, increase CRH and cortisol levels [71, 72]. Read this post to learn about CRH and the negative effects of stress.

14) Thyroid Hormone Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis primarily works to maintain normal circulating levels of thyroid hormones and is responsible for the regulation of metabolism [73, 74].

The hypothalamus senses low circulating levels of thyroid hormone and responds by releasing thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). TRH then stimulates the pituitary to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH further stimulates the thyroid gland to secrete thyroid hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine).

Quality sleep inhibits TSH secretion in humans, while sleep loss increases TSH, T3 and T4 levels [75, 76, 77, 78].

TSH levels increase with acute sleep deprivation but may decrease with chronic sleep deprivation [79]. The increase in TSH suppresses reproductive functions.

More research is needed to understand how sleep and thyroid hormones interact.

15) Testosterone Levels

Studies suggest that in young adult men, testosterone levels begin to rise upon falling asleep and reach peak levels over the first course of REM sleep. Once at its peak, testosterone levels remain the same until awakening [80, 81]. The extent of testosterone spikes during sleep and drops during wakefulness varied between individuals [82].

Sleep deprivation is thought to disrupt this natural rise and fall in testosterone levels. For example, total sleep deprivation reduces testosterone levels in men [83, 84]. This reduction may be dependent on age, with a greater reductions in older men [81, 85].

In a clinical cohort study, men with lower testosterone levels also had lower sleep efficiency. Larger human studies are needed [86].

16) Estrogen Levels

Estradiol (the main type of estrogen produced by the ovaries) balance is essential for the maintenance of reproductive health in women. In women of reproductive age, partial sleep deprivation and a variable sleep schedule increased estradiol levels by approximately 60% compared to non-sleep deprived women [87].

However, in late reproductive age (perimenopausal) women, poor sleep quality was associated with lower estradiol levels [88].

In another study, both pre- and post-menopausal women with sleep-disordered breathing had lower estradiol levels compared to age- and cycle-matched women without sleep-disordered breathing [89].

17) Fertility in Women

Sleep loss elevates several pituitary hormones, which interfere with normal reproductive functions in women.

In reproductive-aged women, an increase in TSH (as seen in hypothyroidism) due to sleep deprivation is hypothesized to cause several reproductive issues including problems with ovulation (anovulation), recurrent miscarriage, the absence of menstruation, and irregular menstrual cycles [90, 91].

In addition, high TSH levels may increase prolactin, which is associated with anovulation, polycystic ovary syndrome, and endometriosis [92].

High luteinizing hormone (LH, typically elevated in polycystic ovarian syndrome) may also underlie infertility in some women. Researchers suggest that healthy sleep keeps LH within normal, although fluctuating, levels [79]. Limited evidence states that sleep deprivation might increase the fluctuation of LH, with overall higher than healthy levels [87].

18) Growth Hormone

The impact of sleep on growth hormone in adults remains largely unexplored. In healthy young adults, experimentally induced slow-wave sleep resulted in an increase in growth hormone release [93].

In another study, average growth hormone levels were higher during slow wave sleep compared to other sleep stages [94].

Scientists found that growth hormone levels also seem to increase during naps but more so during afternoon naps than during morning naps [95].

Sleep & Digestive Health

Sleep deprivation appears to worsen the symptoms of all digestive disorders [55].

19) Stomach Protection

During sleep, defensive mechanisms against stomach ulcers increase while stomach acid secretion decreases [96, 97, 98].

During slow wave sleep, smooth muscles in the colon contract less, so this phase of sleep is considered the “rest period” for the colon.

In animals, partial sleep deprivation has been shown to compromise stomach lining integrity by [99]:

- increasing stomach acidity

- increasing blood levels of gastrin (a hormone that stimulates stomach acid secretion)

- increasing histamine

- increasing norepinephrine

- decreasing stomach mucosal blood flow

This hasn’t been explored in humans. Nonetheless, scientists think that sleep deprivation might damage the stomach and act as one of the risk factors for ulcers.

Healthy sleep may protect against ulcer formation, as women who sleep more are less likely to get peptic ulcer disease. This has yet to be verified in larger studies [96].

20) Bowel Function

Sleep disturbances are common among irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients [100, 101]. IBS is associated with an increase in CRH levels, which reduces deep sleep and increases REM sleep [102].

In one study, IBS patients’ symptoms decreased when subjects slept better [103].

Disturbed sleep also has been suggested to have an adverse effect on bowel function [104, 105, 106].

In Crohn’s disease, an increase in IL-6 levels caused by sleep deprivation seemed to worsen symptoms [55].

Lastly, a cross-sectional study found a nearly 3-fold increased risk of bowel disorders in patients with insomnia. Multi-center studies are required [55].

Sleep & Cancer Research

The link between sleep and cancer is still unclear. We’ve outlined some of the existing research efforts below, but far more work is needed.

Sleep problems such as difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep, poor sleep efficiency, early awakening, and excessive daytime sleepiness are prevalent in patients with cancer [107].

Meta-analysis studies suggest a positive association between long sleep duration and colorectal cancer [108].

Both extreme short and long sleep duration moderately increased the risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women [109].

A cohort analysis in women suggests that longer sleep may be associated with an increased risk of estrogen-mediated cancers, though this remains unconfirmed [110].

One group of authors suggested a link between less than/equal to 6 hr of sleep and the risk of prostate cancer, while sleep greater than/equal to 9 hr was linked with a lower risk [111].

Both short and long sleep durations have been associated with breast cancer [112, 113].

Researchers hypothesize that sleep duration may influence breast cancer risk possibly via its effects on melatonin levels. Naturally-produced melatonin is thought to activate some cancer-fighting pathways, though these have not been confirmed in humans [114, 115, 116, 117, 118].

Melatonin production is closely related to sleep duration. Night-shift work disrupts sleep patterns and thus decreases melatonin levels. Some researchers believe this may explain why night-shift workers have higher cancer risks, but solid data are lacking to back them up [119, 120, 121].

In addition, sleep is also thought to support health by: